But when tariffs are unleashed, as businesses are learning, things don’t always go as expected. Therein lies a cautionary tale of the uncertainty in store for other industries as the Trump administration’s latest tariffs took effect Friday against hundreds of Chinese imports valued at $34 billion, including semiconductors, farm machinery, medical devices and aircraft parts.[…]

Click here to view original web page at www.latimes.com

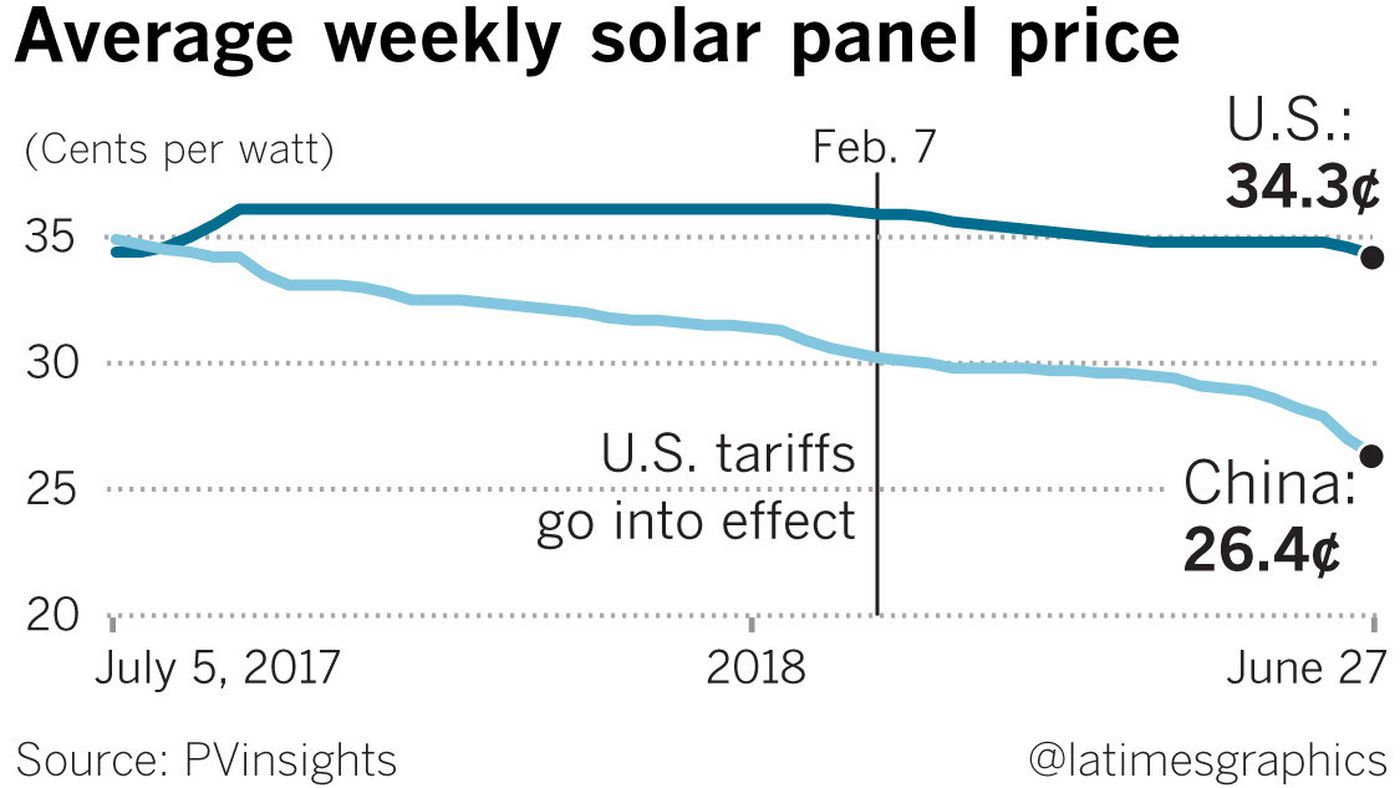

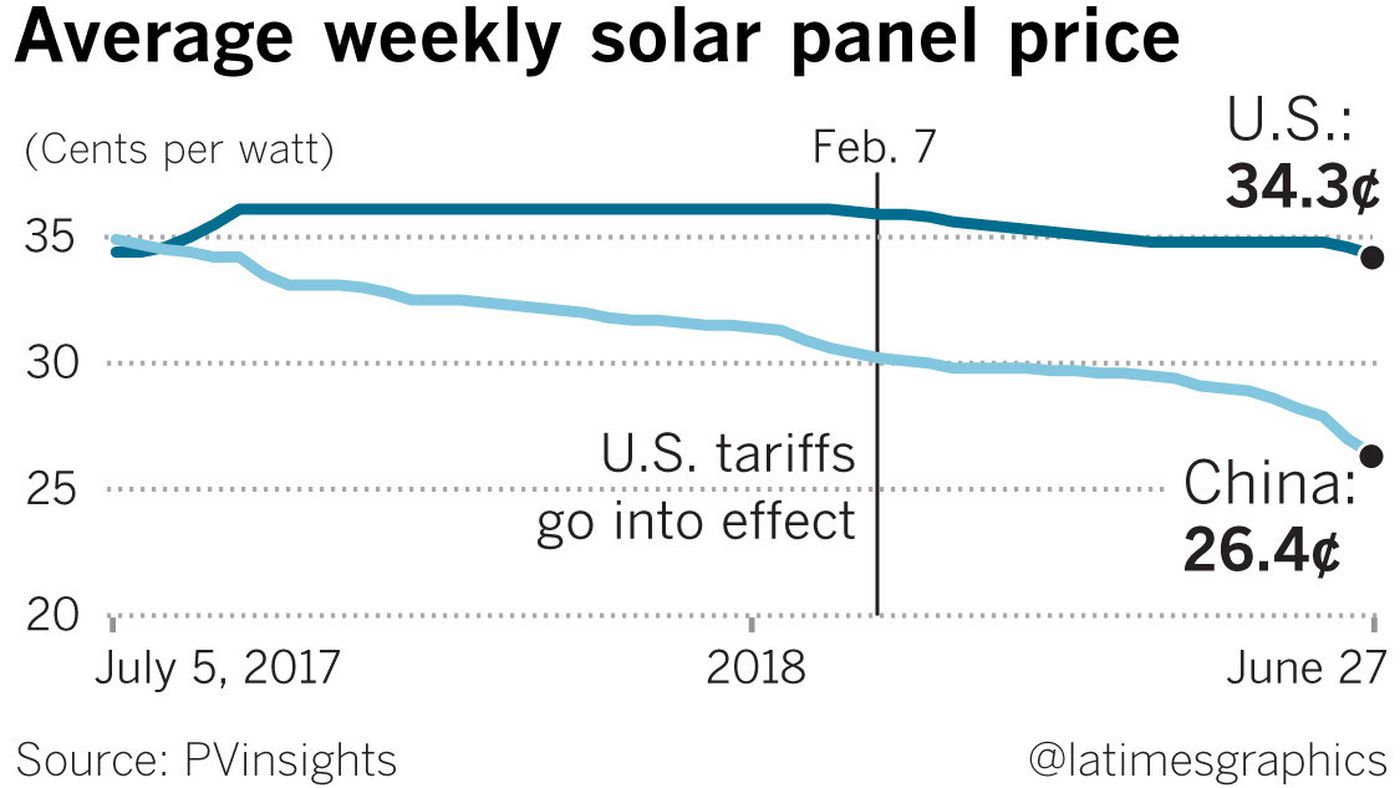

Prices on solar panels did rise last summer as the Trump administration publicly considered the tariffs, mostly on imports from China and other Asian countries. That caused U.S. companies to scramble to purchase as many foreign panels as they could to beat the looming duties.

The higher prices led two U.S. manufacturers to say they’d boost production. At least three foreign manufacturers have made plans to open American factories.

But then, on May 31, China surprisingly slashed its solar subsidies and incentives. The sudden reduction in demand led to a global oversupply of solar panels that further fueled the price drop that began after the tariffs took effect in February.

The upshot: Prices in the United States now are back where they were last summer and worldwide prices could tumble as much as 35% this year, analysts say.

“We’re still really reeling from the impact,” Bernadette Del Chiaro, executive director of the California Solar & Storage Assn., said of the tariffs. “Almost 50% of the roiling and disruption comes from just the unknown and the uncertainty.”

The experience over the last year with the U.S. solar tariffs shows that the straightforward goal of boosting domestic manufacturing often conflicts with the real-world flow of goods. Once you launch a trade war, it’s very hard to control the consequences.

That was on full display recently when Harley-Davidson Inc., said it would move some production abroad to avoid tariffs that the European Union slapped on U.S. motorcycles. Those levies were in response to Trump administration tariffs on imported steel and aluminum that were designed to boost American manufacturing.

Solar industry executives and workers are feeling whipsawed as they also deal with the fallout from the tariffs on steel and aluminum, materials that are used in the racks that hold solar panels on rooftops and on large solar farms.

“There’s no question it’s had an impact on the size of the American solar market,” said Tom Werner, chief executive of SunPower Corp., a San Jose-based company that makes and installs solar panels.

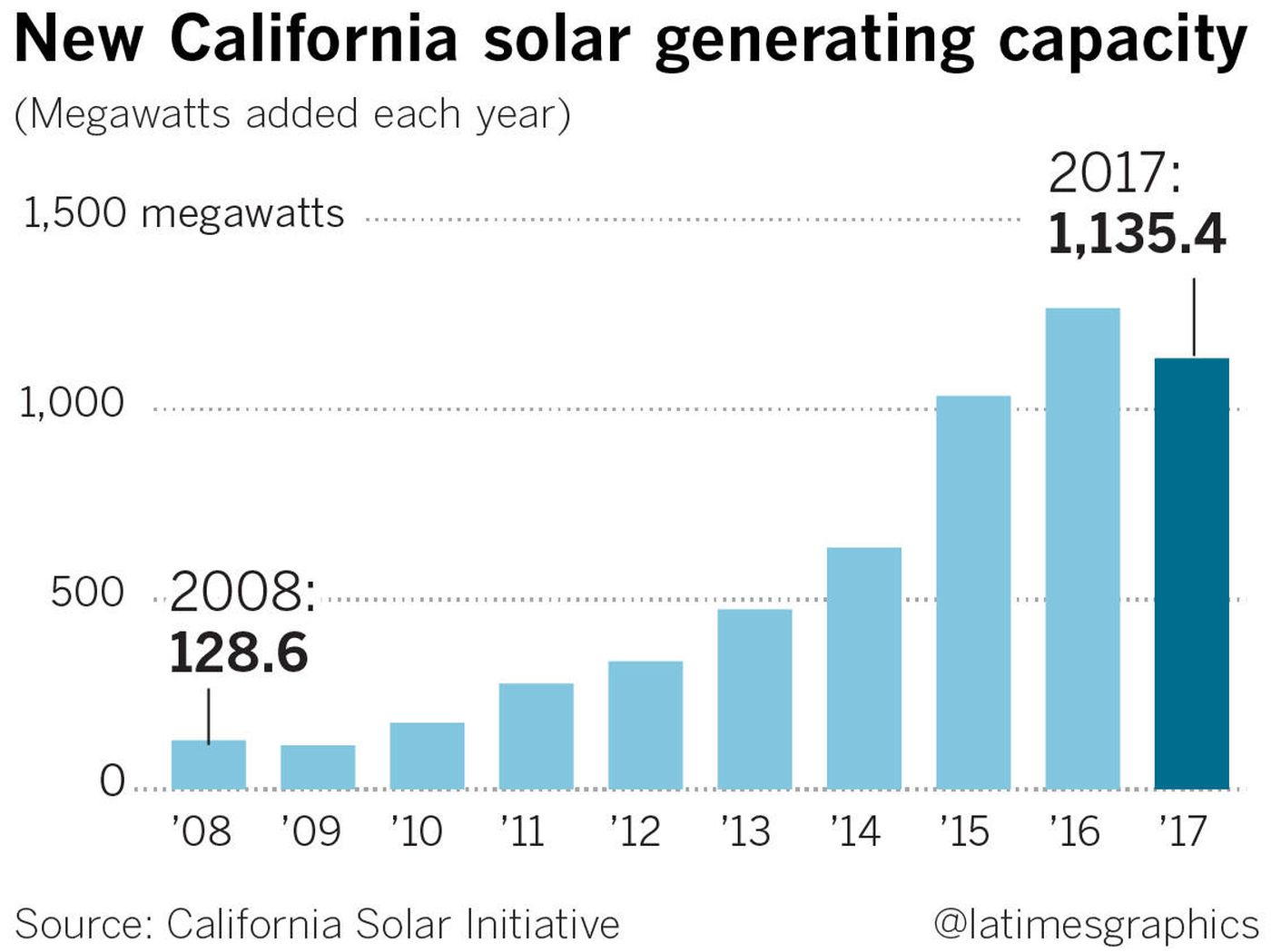

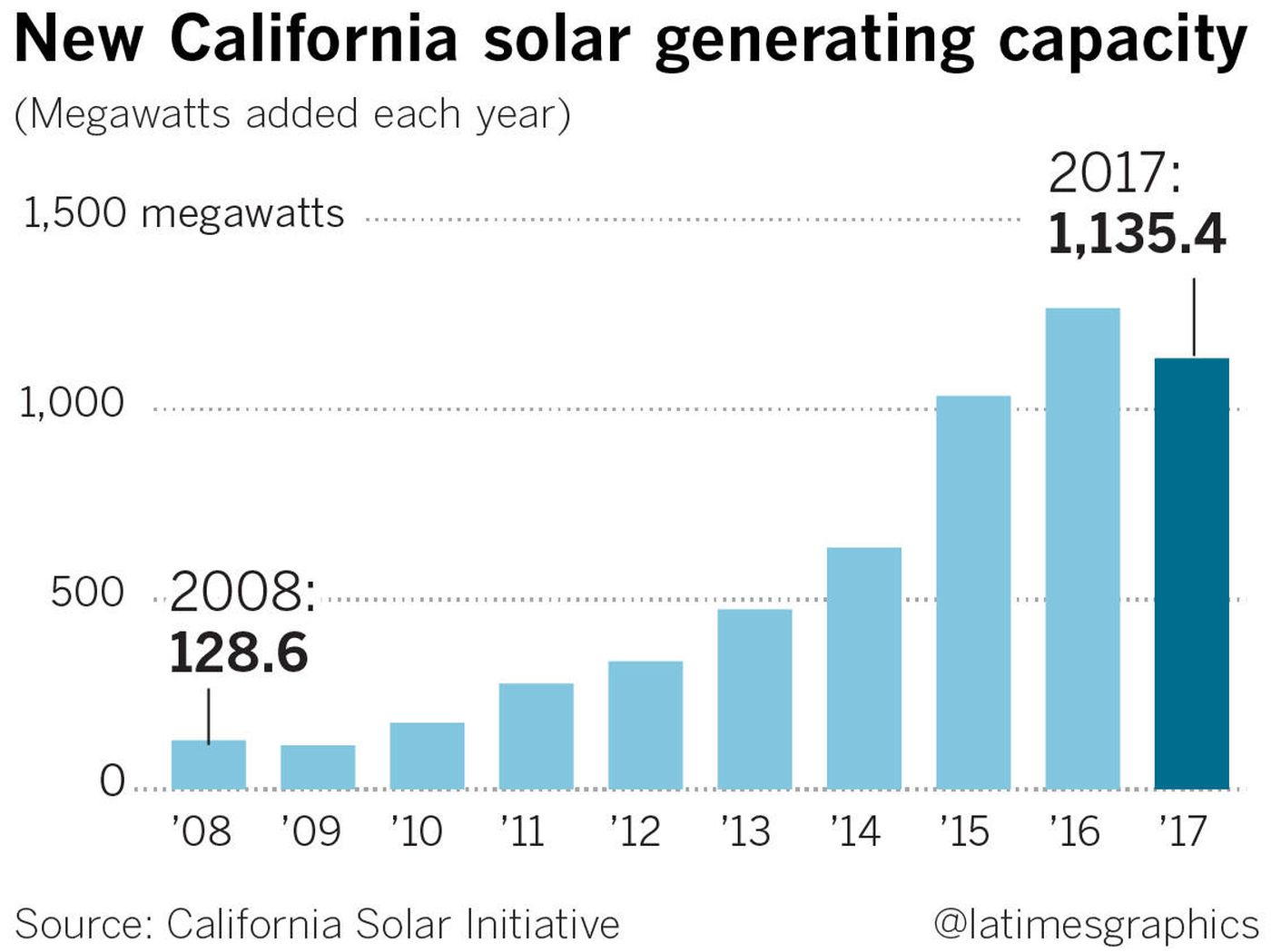

New solar power generating capacity declined last year in California for the first time since 2009, according to state figures. And Bloomberg New Energy Finance, which uses proprietary data to analyze industry trends, recently estimated the global solar market could shrink this year for the first time ever.

farm machinery, medical devices and aircraft parts.

“There’s just a lot of demand that could have happened that is not going to ultimately be realized because of these tariffs,” said Cory Honeyman, associate director of the U.S. solar research practice at GTM Research, a market analysis and advisory firm. The tariffs led the firm to reduce its forecast for additional U.S. solar generating capacity during 2018-2022 by 11%.

The tariffs and overall trade tensions almost certainly were factors in the decision by China’s leaders to cut its state support for solar energy development.

China had been furiously pumping money into green energy projects, accounting for nearly half of the $280 billion invested in renewable energy projects in 2017, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. China added 50 gigawatts of solar power last year, accounting for more than half of all global solar photovoltaic module installations. The country now has a kilometer-long highway paved with solar panels, the world’s largest floating solar farm, and panels atop countless roofs in villages and cities.

“Even a pig will fly if it’s hit by a tornado,” said Liu Shisheng, 25, using a Chinese expression to describe how his fledgling 20-employee business in central-eastern Wenzhou had soared by installing solar panels at homes and businesses.

In April 2017, bankrupt Georgia solar panel manufacturer Suniva Inc. formally asked the U.S. International Trade Commission to impose tariffs on inexpensive imported panels that the company said had crushed its business. The petition was later joined by SolarWorld Americas Inc., an Oregon company, after its German parent — a leading European solar panel manufacturer — also sought bankruptcy protection.

A commission investigation found that the mostly Chinese-made panels, which fueled the solar boom in the United States, were priced artificially low and had severely reduced American solar-panel manufacturing. It recommended that the United States impose tariffs. Trump agreed, and in January, the administration announced hefty levies: 30% the first year, declining gradually to 15% when they end after the fourth year. They took effect Feb. 7.

About 613 megawatts worth of solar panels were imported on average per month over the first half of last year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That jumped about 75% to nearly 1.1 gigawatts a month for the last six months of 2017 as the International Trade Commission considered and then ruled on the tariff case.

After what he called a “banner” 2016 for its work building large-scale solar generating facilities for utility customers, McCarthy Building Companies saw business tail off in 2017 as some clients decided to put projects on hold, he said. That led the company to cut by roughly half the number of people it employs for solar installations, to about 1,000.

Pine Gate Renewables, a solar project developer in North Carolina, also wasn’t large enough to stockpile solar panels, Chief Executive Zoe Hanes said. The company will complete only about half of the 400 megawatts worth of solar projects it had planned to finish this year. Because of that, Pine Gate Renewables didn’t hire the additional 30 people it had planned to add to its 85-person workforce this year.

The Solar Energy Industries Assn., a nationwide trade group, had estimated the tariffs would cost 23,000 jobs in the United States in their first year — a combination of layoffs and positions that weren’t added to an industry that employs about 250,000 people. So far, it’s tallied about 8,000 jobs since the tariffs took effect, said spokesman Dan Whitten.